… You read the papers? Hear what they say?

“You’ll only catch AIDS if you’re black or you’re gay.”

So don’t worry America, you’ll live a long life

Keep your eyes shut to the pain and the strife

There are millions out there that’ll die in a year

But don’t get excited, Don’t shed a tear

Just keep livin’ your lives like it doesn’t exist

‘Til it hits you, then you’ll be pissed …

… So come on home, open your eyes,

Everyone knows a young person who dies.– Lilywhite Lies, by Frank H. Jump © RoughGift Productions/BMI

Frank H. Jump was only 27 years old when he wrote these lyrics of his poignant rap song. As a gay man living in New York in ‘87, he had been diagnosed HIV positive just a year before — told by the doctors that he wouldn’t have much time left…

Although he doesn’t consider himself a religious person, Frank says that at 24, the year he actually got infected with HIV, he had what he considers a metaphysical experience, where somehow an inner voice told him, two years before he got his actual diagnosis, “You have got AIDS, but you will be ok.” Frank is here outside a botanica store, where he was marveling at a beautiful sculpture of Yemanya, goddess of the sea.

Having always dreamed of being an artist, it was the shock of this sudden news that finally prompted Frank into action. If he was going to possibly die soon, there wasn’t a minute to waste — he’d take life more seriously and create something that he could be remembered by. Maxing out the $80,000 on his credit cards, he went shopping for photography and home studio music equipment — taking photos and writing songs. The very day Frank had turned 27, his then boyfriend, activist Eric Sawyer (founder of Housing Works), took him to the town meeting that playwright/activist Larry Kramer had organized to talk about experiences with HIV, and to demand action towards the health crisis. The event included several celebrities, including actor Martin Sheen — who that night would end up crying on Frank’s shoulder, remembering his best friend who had died of AIDS. By the end of that evening history would be made, and the activist organization ACT UP would be created with Frank becoming one of its founding members — incorporating his artistic talents to the cause against the AIDS crisis, with creative collaborations or helping to stage theatrical guerrilla protest “zap” actions. Within the core message of ACT UP (with their slogan “Silence = Death”), and their fight against the inaction of the Reagan administration regarding the health crisis, Frank’s song “Lilywhite Lies” and its powerful message would become an anthem for the organization.

And also a painful one… when we revisit the verse “Everyone knows a young person who dies.” All around Frank — within his circle of friends and support system — people were getting sick and dying every single day. Dreadful calls would come in nearly every day, informing them of another sad end to a loved one or acquaintance. At the dentist practice where Frank was working as an office manager (one of the few that would work with AIDS patients), they would often receive calls from a relative or partner of a patient informing an appointment would need to be cancelled, due to an AIDS-related death. In 1988 alone, Frank lost around 250 people he knew. For a person who wasn’t even 30 yet, within a gay community that was being left to their own suffering by their very own government, it was a tough reminder of the concept of every day mortality —all while the chance he could share that same fate at any moment hovered over him like a dark cloud.

Frank plays the guitar and sings while sitting in his dining room at home in Brooklyn and tells me a story on how “Lilywhite Lies” almost got him a record deal, but he was told “a white man rapping wouldn’t sell.” A few weeks later, Vanilla Ice broke into the music scene and the record company who had said those words to Frank sent an apology letter.

Fast forward to today… Frank Jump turns 54 this week. He’s now been a long-term HIV survivor for almost three decades (more than half his life), and is thankful for having the opportunity to be around this long — creating art and teaching, and having wonderful love in his life. Though he’s not without the common case of “survivor’s guilt”…

Frank shows an older photo of himself when he was only 17. Born in Queens, New York, where he spent most of his youth, he was from very early on a politically motivated, unapologetically flirty and alive young man exploring the city and the fun it had to offer back in those days.

From his beautiful home in East Flatbush (Brooklyn), Frank reminisces about all the different ways he’s had to survive. There’s a certain irony in the fact that in the nearly 30 years he’s had to live with the constant reminder of the virus, he has actually never gotten sick from it. And yet, when he turned 40, instead of a midlife crisis, he had to face his second big survival challenge: battling rectal cancer — requiring chemo and radiation before he once again would beat the odds and keep going through life. All of this, in the middle of a career move that was bringing Frank from the dental practice he had worked for years into education, where he started a class for kids in “movement,” making them play with dance, theater work, motion and imagination…

As Frank sits in an armchair by his living-room window telling stories, I can’t help but watch his body language and energy as much as listening to his words. In a few minutes he can go from shining (with a twinkle of a smile) while speaking with a very funny and charming theatricality, to pausing at some moments — where you may catch a fleeting glimpse of melancholy in his eyes, trying to remember a particular name or situation, and making it a mission not to forget anything important. He describes himself, the AIDS survivor, as “a magical child that never gets old, believes life is beautiful and worth living and vanquishes death, fear and pain” to feel invincible, mostly through the strength he gets from his amazing support system and his art.

As a musician and music lover, Frank loves this vintage jukebox that stands right in front of the main door of the house, welcoming visitors with music and a beautiful light.

That support system has to do with the way Frank cherishes human connections: he remains friends with all his exes, feels proudly about family and life-long friendships (including his special bond with Isabel Celeste — the female voice on “Lilywhite Lies” — and her daughter, Hollywood actress Rosario Dawson, whom Frank adores and considers his niece). But there are two key people in Frank’s life that have shaped his quest to survive everything: on one hand, the man Frank calls “his life boat”: his husband and partner of 24 years Vincenzo, with whom he’s built a beautiful home and great memories — including a very well-publicized wedding with several other couples in Toronto (Canada) that made the media rounds 10 years ago. With his roller-coaster of a personality, Vincenzo manages at once to be there with compassion for Frank when he’s had a hard time, while at the same time pushing him to “snap out of it” if Frank chooses to dwell too long in a mood.

Frank in front of a PFLAG “Stay Close” campaign poster featuring him and his niece, actress Rosario Dawson. He jokingly says that this is his own version of a fading ad, since the poster acquired this washed out tone, in the style of a 70’s photograph, after a few years.

Frank Jump and his husband, Vincenzo Aiosa at their home in Brooklyn. The two have been together and in love ever since the first minute they met, back in 1990.

The other essential person in Frank’s life has been his mother Willy. Originally from Amsterdam, she remained an extraordinary and supportive ally in Frank’s path, teaching him he could do anything he dreamed of. From the moment he was able to come out to her when he was 11 and throughout his life, his mom became a proud supporter of LGBT rights, by Frank’s side in a march in Washington in 1979, and becoming a PFLAG mom (Parents, Friends and Family of Lesbians and Gays). Even during the AIDS crisis, when many were estranged from their families, Frank’s mom was always there, for him and others. Today, as she’s battling Alzheimer’s, she’s visited every other day by Frank in the lovely nursing home she’s living in. Frank describes how one of his favorite things is the joy on his mom’s face when he enters the room. And I am honored to witness it one afternoon as I accompany him for a visit. As Frank chats briefly with some other residents of the home, his mom looks at him with heart-melting pride in her eyes — a bit emotional, and you see genuine happiness as she watches him. It’s as if every visit is somehow a fresh experience in her mind. In a more intimate conversation in her room, they laugh together, very affectionate to one another and their matching smiles reveal years of layered complicity that are at once uplifting and touching.

Frank and his mom, Willy Jump, in an affectionate moment together while at her room in the nursing home she’s currently living in. Frank visits her there every other day and expresses his sadness upon seeing some other residents that never receive any visitors. He tries to talk to them too when possible.

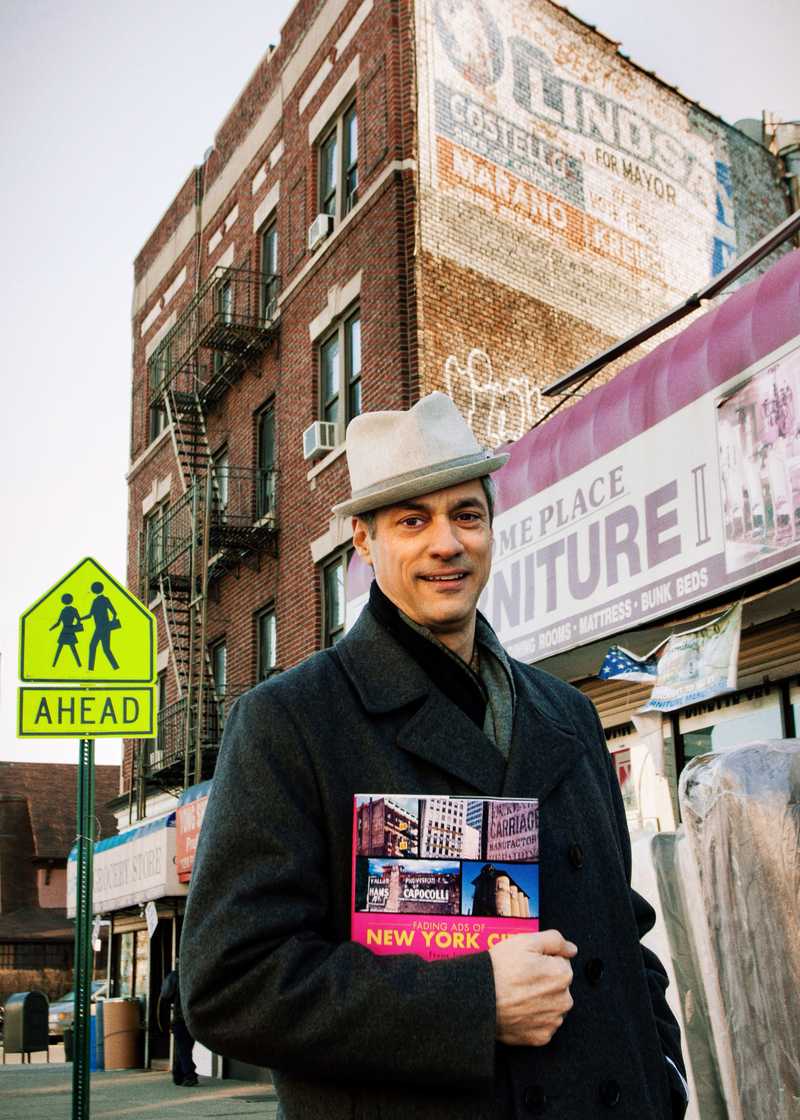

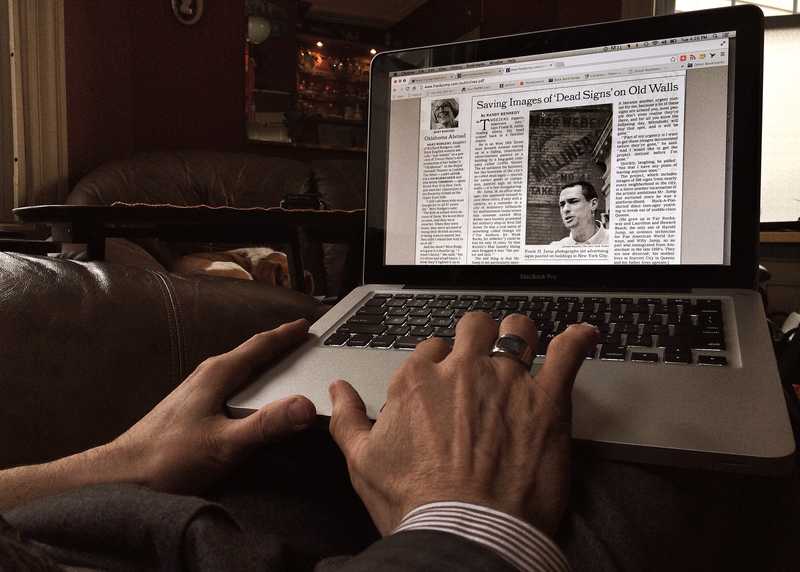

Unintentionally, the situation with Frank’s mom has come to provide his life’s artistic quest with an additional layer of meaning and purpose. The survival of memory, of identity, has always been at the core of Frank’s best known project, the “Fading Ad Campaign.” It’s a documentary study born in the days when Frank was doing his Bachelor’s degree in Arts at SUNY/Empire State College, where he had a serendipitous encounter in 1997 in Harlem with a vintage Omega Oil sign on the side of a building he photographed. Frank discovered the city was full of these old, hidden school billboard ads, that once had stood up as shiny beacons of a message, the soul of a product or business now long gone. But those signs, faded by the sun and the years, have overcome their life-expectancy and become a reminder of their moment in the past, providing context of past styles and social trends in an older by-gone New York City and America. Frank started photographing them trying to get their best side (“as in capturing an old diva,” he would put it), and when it clicked for him that this was a powerful metaphor of his own survival and enduringness, he knew he had found his life’s artistic mission. The project has been exhibited, featured in the front page of The New York Times’ Metro section in 1998 (among many other media), and published in the book “Fading Ads of New York City” — and it continues on Frank’s blog, where it’s sparked a network of collaborations with contributors from many other cities.

Frank stands in a corner of East Flatush, Brooklyn, with a copy of his book, “Fading Ads of New York.” Behind him, in the top right, there’s one of the ads in the book, in support of Lindsay’s mayoral campaign.

There’s an additional way in which Frank’s quest to create a preserving imprint that survives time has materialized. While he and Vincenzo haven’t had any children of their own, Frank has been helping to shape the paths of many kids as an educator for almost 15 years, often working with kids in underprivileged neighborhoods. He’s currently the science and technology teacher at PS 119 Amersfort School. The day I visit his class, he’s teaching the kids how to find their houses and see them on “street view,” as well as The White House. His students behave and at times seem to compete for Frank’s attention or help. He’s gentle, compassionate and open with the children. Frank cheerfully recalls how one of his students recently told him he had “Googled” Frank and seen a photo of him kissing a man. “Not a man! My husband!” was his reply. He makes the kids laugh and he’s proud of the way they adore their “Mister Jump.”

Frank in a distended moment while his young students look at the street view of their own houses on Google maps.

Frank treasures the joy in the children when he teaches them something new that amazes them, the hugs at the end of a lesson, the sparks of genius they incorporate in their writings, and the ongoing connections he’s kept with his students over the years. He’s received letters as much as a decade after a student graduates telling him of their life progress and how he inspired them in their profession. Or those from former students who had written about suicide in their poetry while at school and, after being counseled by Frank back then, are now sending photos of their own children with a “thank you” note. Frank considers himself “blessed” to be able to work with children, who give him a sense of meaning that pushes him to want to move forward.

After the bell rings for the end of the class, Frank poses with his group of 3rd graders in the technology class at PS 119 school.

Frank thinks his story can give hope to a young person that may be just grappling with receiving a recent HIV+ status. His advice to them would be the same he gave to himself: “Tomorrow is not a guarantee, so DO IT NOW. Look around yourself and identify what is meaningful to you and make it an inexorable task to continually define and redefine yourself and your place in the world. Not everyone is aware of their innate talents that lie buried beneath the surface, but it’s there if you scratch at it. Enjoy the itch.”

Frank drinks a cup of apple cider after coming home from the school where he teaches. In the house’s garden, a striking visual metaphor — seeing Frank next to a statue of Saint Lazarus, the man who was resurrected.

Frank will always remain a survivor, one who’s overcome the threat of living more than half his life with HIV, cancer, a period of bankruptcy while repaying his debt, and crushing emotional losses. Although being way too busy living life and creating, he has never allowed himself to forget. He admits that today, while getting to that age when yet again he’s starting to lose friends to now “age-related” illnesses and coping with the situation of his mom, he can find himself getting emotionally exhausted at the end of the day. And that sometimes the heaviness of the melancholy of the past — the memory of all those lives who were lost — comes back upon him like a tidal wave. He hopes those moments find him being at home by himself, where he can cry and cleanse. He’s kept correspondence through the years with other long term HIV survivors, people who shared his experiences. He intends to hopefully start a new photo project that documents the experience of living as an HIV+ person in a “community of survivors” — and the long-term effects of anti-retroviral medications on aging people with HIV, living in a city that he thinks is “as ill prepared now to deal with the problem as it was when the crisis first hit.” He considers them survivors “like fading ads, painted once with bright colors that have since faded to softer tones, never having expected to last this long, and yet still here to communicate and influence our society.”

Frank’s hands on his computer, as he shows the 1998 New York Times article about his Fading Ads project, that was being exhibited at the NY Historical Society.

In any case, with his accomplishments and life story, Frank has without a doubt left an imprint that has allowed him to escape the final verses of his beautiful anthem song, that referred to the untold stories of those who fell victims of AIDS in the worst of the crisis:

“Don’t wanna be a number…

Don’t wanna be what they want me to be

Another number.”

What an incredible, inspiring story. Creativity, friends and connections are so important, and it’s especially heartening to see how they’ve been such a part of Frank’s journey. Not just surviving, but truly thriving.

Thank you so much, Richard! I appreciate the comment. Indeed, Frank’s story is heartening and inspiring in many ways. Still today, to me…. how much passion he puts into everything he does.